- Home

- Hilary Sloin

Art on Fire

Art on Fire Read online

Art on Fire

A Novel

Hilary Sloin

Ann Arbor

Copyright © 2012 Hilary Sloin

Bywater Books, Inc.

PO Box 3671

Ann Arbor MI 48106-3671

All rights reserved.

By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of Bywater Books.

Bywater Books First Ebook Edition: March 2013

Bywater Books First Edition: October 2012

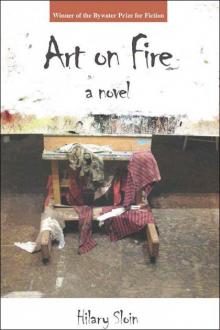

Cover designer: Bonnie Liss (Phoenix Graphics)

Cover photo: Barbara Hadden

ISBN: 978-1-61294-032-8

This novel is a work of fiction. Although parts of the plot were inspired by actual events, all characters and events described by the author are fictitious. No resemblance to real persons, dead or alive, is intended.

I dedicate this story about love and art and death to my canine companion in all those endeavors for fifteen years, Zen. She was the most beautiful soul I have ever encountered, and I am fairly certain she will never be rivaled. She was with me all through the writing of this book. She died on July 21, 2011, at the age of 15. Not a day goes by that I don’t feel her absence and thank whatever force it was that brought us together.

Contents

Art on Fire

March 12, 1989

A Cry from the Attic

Chapter One

Woman and Stool, 1988

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Rake, 1986

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Emergency Room, 1986

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Cigarette Burns, 1987

Chapter Ten

What She Found, 1983

Suburbia Dissected

Chapter Eleven

Woman Reclining on a Blue Couch, 1984

Chapter Twelve

The Lisa Trilogy (Lisa Gone, Genius, Virgin), 1982

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Bunyan, 1988

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Study of White Figure in Window, 1988

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Reality Has Intruded Here

Reality Has Intruded Here, 1989

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

This is How She Looked in the Morning, 1989

Chapter Twenty-Four

Hilary Sloin

Acknowledgments

There’s no place like home, and many a man is glad of it.

F. M. Knowles, A Cheerful Year Book

On March 12, 1989, at 3:12 a.m., a greedy fire erupted in an otherwise placid neighborhood, decimating the modest house at 312 Riverview Street,1 along with its residents: Alfonse and Vivian DeSilva, Isabella DeSilva, and Francesca deSilva,2 foremother of pseudo-realism and arguably one of the greatest American painters.

Approximately nineteen of deSilva’s paintings were destroyed in the fire. Their monetary worth is undetermined; their artistic value, immeasurable.

The perspicacious reader will visit the Francesca deSilva Memorial Museum in Truro, Massachusetts, where the thirteen paintings discussed in this volume hang side by side, to devastating effect. This is how the work was meant to be experienced, and this encounter, more than any words you will read in any pages, provides the truest testimony to deSilva’s genius.

A Cry from the Attic

New Haven, 1974–1981

Chapter One

Unlike her sister Isabella, whose genius was of a flamboyant variety, Francesca deSilva exhibited no early signs of excellence. At best, she displayed a vague propensity for mechanical repair: tinkering with broken radios and jammed doorknobs, devoting entire afternoons to the assembly of a new purchase—a fan, a chair, a light. A sturdy, somber girl of few words and a solitary nature, she spent her ample free time playing along the river that ran across the street from her home. It was a wide, brisk river that rolled around bends and over hills, splashed into smooth, open pools, some of which were deep enough to float in. She passed many hours on its sandy shores, lying flat with her eyes closed and listening to the inside of the world.

Each day after school, upon stepping off the bus, Francesca waited—tying and untying her shoe or searching for a stick of gum—until the other children had dispersed. When she was certain of her solitude, she swung her book bag across her back and spilled down the embankment, twisted around prickers, and hopped rock to rock over the gelatin swamp, until she arrived at her destination: a slice of river beach, far from her house, smoother than the shores of the Long Island Sound. There, she stood at the shore and let water lick the rubber tips of her sneakers.

She longed to be Sam Gribley, the boy in My Side of the Mountain:3 to run away from home and survive on instinct, live alone with a wild animal she’d tame. Bathe in the river, stew berries. Instead of living inside a hollowed-out tree as Sam had, Francesca would furnish a hut. She’d drawn up specs and pilfered a sheet of chamois from her father’s collection to make a door. But being a pragmatic child, and having long been accustomed to delayed gratification, she’d resolved to start construction on the perfect day, when the sky was clear and the air crisp, when she could be certain several hours preceded nightfall. When at last this day arrived, Francesca scoured the woods like a rabbit, piling fallen branches on her outstretched arm. She sought out the evergreens, whose green needles clung like curtains long after the sap had dried up. With these branches she would form the walls of the hut; for the base, she needed thicker, sturdier boughs of oak or maple. She worked without pause, running up the embankment and back down, wiping her forehead with the back of her soiled hand, growing her two piles—evergreen, miscellaneous hardwood—higher and higher, until they were as tall as Francesca herself.

The day grew dark suddenly, the way it does in September in New England, as if winter had been hovering the whole time, picking its moment. Without warning, she could see nothing. The river was just a rushing sound to her right; the woods were black and filled with sudden slapping sounds. She scrambled back through the marsh, swatting at prickers, twisting her ankles into soft spots. Exhausted, she scaled the embankment on hands and knees.

A blaring porch light announced her house on the other side of the street. She plodded across the road and onto the lawn, ignoring the walkway her father had carved in the center of the tidy, square lot. Blinking against the sudden brightness, she pressed the doorbell, then held onto the threshold and emptied pebbles from each shoe onto the freshly swept porch. Twigs perforated her dusty hair. She cupped her hands and peered into the picture window. Through her own reflection she saw bowls of chips and candy set out on the lucite coffee table. The sheets had been removed from the furniture.

Vivian DeSilva opened the door, erect as a sailor in her navy blue dress, a gold chain-link belt tight around her narrow waist. Her burgundy hair was piled on her head, twisted and tucked in a complicated design. Thick, orange paint made her lips glow in the dusk.

“You look nice, Mom,” said Francesca.

Vivian dragged her gaze down until it found Francesca’s face. “Oh, Francesca!” She covered her mouth and clasped the girl’s small

shoulders, pulled her into the house. “Alfonse! Alfonse!” (louder the second time). “Honey, don’t touch anything,” she said, her face collapsed with worry. She held Francesca’s dirty hands in the air.

Alfonse, also gritty after a long day planting perennials around a new shopping center, trotted down the stairs and arrived in the foyer. “You rang, Madame.” He roughed up Francesca’s dusty hair.

“Honey, go get your toothbrush,” she told Francesca. “Papa will bring you to Grandma’s.”

“I don’t need a toothbrush. Grandma lets me use hers,” said Francesca, boasting.

Vivian looked at Alfonse. She popped her eyes wide and opened her palms. “Well? What are you waiting for? I have eleven dinner guests coming in an hour. Could you lend me a hand here?” Alfonse rubbed her back and kissed her spuriously on the cheek, then rested his heavy hands on Francesca’s small shoulders. “Let’s go, Tiger.” He guided her through the kitchen and out the back door.

In an effort to give a leg up to the lagging social development of her older daughter, Vivian had located the families of four other child geniuses in Connecticut and invited them for dinner. But now that the event was imminent, she was stricken with a pervasive sense of doom. She trotted to the top of the stairs, then knocked cheerfully on Isabella’s door. “Bella!”

Slowly Isabella pulled back the door. She stood solemn and erect, in an old brown sweater and black wool skirt. Vivian half-recognized the outfit as the one she’d worn to her father’s funeral eleven years before. The skirt hung to Isabella’s ankles, punctuated by white knee socks and misshapen black shoes. “What are you wearing?” she demanded.

“My outfit.”

“I see that! But we have people coming over.” She pressed two fingers of each hand to either temple, holding the sides of her head together as if they might come apart.

“This is what I’m wearing to the party. I’m dressed as someone important. A great hero of this century.”

Vivian forced a chuckle despite the fever of panic beginning to rise inside her. She couldn’t stand how much she loved this child. “Okay, Miss Smarty Pants. Who? Who are you dressed as?” She crossed her arms and tapped the floor with her foot.

“Guess.”

“Oh, I don’t know . . . Annie Sullivan.”

“Wrong.”

Vivian searched her watery memory for dowdy female heroines. “Virginia Woolf?” she asked, hoping she wasn’t entirely misinformed. It wasn’t easy, being less intelligent than your eleven-year-old daughter; she shook her head, enjoying every moment of it. Brains like these had to come from somewhere, and certainly Alfonse’s family hadn’t cultivated them in the pizza kitchen in Wooster Square.

“I’ll give you one hint,” said Bella. “I live in an attic.”

Vivian hesitated, twisting her face in concentration. “Not your sister . . .” she said, blanching with dread.

“What? Are you nuts?”

“Oh! Oh!” Vivian snapped her fingers, thinking fast. “Emily Dickinson!”

“She didn’t live in an attic,” Isabella sighed, then brightened. “Okay, really, really, the last hint. Put on your thinking cap.” Vivian gestured as if she had. “I have a boyfriend named Peter,” certain this was the give-away.

Vivian was distracted by thoughts of the lasagna sizzling in the oven, whether Alfonse would return in time to shower, how to get Isabella out of this ridiculous outfit and into her party dress. “I’m sorry, pumpkin. You’re much smarter than your old Mom.” She guided Isabella into the bedroom.

“Duh. Anne Frank. I’m Anne Frank.”

“Of course you are! Anne Frank! We should show your grandmother. Did you know she was once in a play about Anne Frank?”

Isabella shrugged, unimpressed. “I’ve written a play about Anne Frank.” She lifted her arms and waited for Vivian to pull the sweater over her head.

Francesca rode with her body pressed against the car door, the handle digging at her hip. She breathed on the window, made circles with her finger. Already she could smell the ladies’ itchy perfume, hear the cracking of mahjong tiles and gum. She imagined her entrance: The game would be underway, so that anything she did would garner a sigh of feigned exasperation. She’d call out Hi! and run down the hallway to her grandmother’s bedroom, throw herself onto the bed, and bury her nose in stinky fake furs. Then she’d hole up in the dark TV room, eyes fastened to the Friday night lineup. During the commercials she’d wander out to the kitchen and stand around coyly, stab melon balls with toothpicks, bite into the Russell Stover chocolates in search of caramels. “Gross,” she’d say when confronted with a dribble of strawberry cream or rum. (One of the ladies would finish the confection so it wouldn’t go to waste.) She’d wear her grandmother’s bifocals with the rhinestones in each corner, walk around the card table with her hands extended in Frankenstein position, the cool chain tickling her neck.

She did anything for the ladies’ attention, doled as it was in scraps between hands. She fetched their pocketbooks and refilled their glasses with Tab, emptied ashtrays, and closed the window if it grew too chilly. They teased her about being a tomboy, pinched and kissed her, made her feel loved and abused at the same time.

“Francesca, what you do in the woods?” Alfonse inquired.

“Nothing.”

The houses in her grandmother’s neighborhood were separated by faded ribbons of grass the color of limes, just big enough for a lawn chair, a kettle grill, maybe a dog. Alfonse turned onto the street without signaling. The driver behind him held down the horn, swerved around the left side, waved his middle finger in the air. “Idiot,” Alfonse muttered, imagining Italy where, he imagined, people were civilized, where a little blinking light would not be necessary to inspire common sense. He glanced at Francesca. Her face was turned away from him. He snuck a look at her thick, dark hair, like his, a pointy chin, again like his, and a take-charge body, sturdy and tall, capped off by thick hands and grounded legs.

“Do you play with the frogs?” He glanced at her. “Are you a friend to animals?”

Francesca turned and looked at her father. She felt ashamed, as if he had guessed something simple about her, something obvious. “I like animals,” she said nonchalantly.

“I, too, have always loved animals. When I was a boy, I used to feed the squirrels, which you can imagine went over big with my mother.”

He rolled his eyes. “They’re rodents, you know.” He stopped at Evelyn’s driveway. “Do you play in the river?”

“Mostly.”

“Alone? Or with friends?”

“Alone.”

“How about I come sometime? We could play in the river together.”

“Okay, sure,” said Francesca, looking up at her grandmother’s picture window. The light was on over the kitchen table. She could see it through the threshold. “It’s really kind of boring.” There was nothing in life less boring, she knew, nothing so full of possibility, with such a strong pulse. To bring her father there would interrupt the gentle ecosystem. He could not see the hut or he might start to suspect her larger plan. No matter; she knew from past conversations of this nature that he would forget all about this one.

“Hey, I know.” He pounced on the brake. “How about we go for an ice cream?”

“No thanks, Papa.” Francesca hopped out and slammed the door. She could hardly wait to be inside the small, warm house and see what treats her grandmother would produce—always magically—from some obscure cabinet or cubby beneath the oven door.

Stiff as a stick of stale gum in her velvet jumper and white bow tie, Isabella sat at the kitchen table and watched Vivian tuck her head inside the oven to check on the lasagna.

“Sylvia Plath committed suicide that way,” she said.

“That’s certainly not what I’m doing.” Vivian backed out at once and wiped her forehead with the silver oven mitt.

Isabella sighed. She pilfered a Hershey’s kiss from a tulip-shaped bowl that was filled to the brim, unwrapped the cand

y, and tried to stand it upside down. No luck. She bit off some of the point to flatten it, then tried again. Some days, this being one of them, she hated to talk. She hated the sound of her voice, the scratchiness at the back of her throat, the feeling of her teeth slamming down on each other. Other days, there seemed to be a dearth of words in the world. On these days, she’d read entire books aloud, just to hear her voice dip and climb, reveling in her perfect articulation. Then there were the confusing, disorienting days, the ones that started one way, then switched to the other, leaving her breathless, confounded as to how to slow the busyness in her brain.

“Tell me about Anne Frank,” her mother said.

“You know about Anne Frank,” she whined and pulled on her collar. She took two more chocolate kisses, plugged each into a nostril, then an ear, then held them up to her nipples.

“So tell me again,” Vivian turned. “Bella! Stop that. Those are for the company!”

Alfonse opened the back door and wiped his sneakered feet thoroughly over the spiked welcome mat. He greeted them with swollen eyes, giddy from having had a little cry after he’d dropped Francesca off. He’d succumbed to his ever-lingering, rarely conscious feeling of failure as a parent. He was more willing to acknowledge his shortcomings as a husband, largely because he felt he wasn’t to blame for the bitter marriage. On the other hand, his inefficacy as a father was only partly Vivian’s fault; he knew he was culpable, and couldn’t bear it.

“Oh good,” said Vivian. “Isabella’s about to tell us the story of Anne Frank.”

“Holy cow. That’s terrific!” He patted Isabella’s head and ran upstairs to shower before the company arrived.

They filed in at 6:30, children first. Chips and dip, M&Ms, and chocolate kisses were set out on the coffee table for the kids, pinkish port wine cheese in a plastic tub and Triscuits for the adults. The frightened children scattered, fists clenched at their sides, eyes averted—especially from each other—checking every instant for their parents’ faces to make sure they hadn’t been left behind.

Art on Fire

Art on Fire